Summary of Command Line Argument Handling in C/C++

Some time ago, when looking through the Linux kernel code, I came across the handling of module parameters, which I found quite ingenious. It made me want to explore how to handle command-line parameters in C more effectively. The code used in this article can be found here aparsingThe code supports compilation and execution on Windows, Linux, and Mac OS X. For detailed compilation instructions, please refer to the README.md file.

getenv

The standard library provides us with a function getenv, which literally means it is used to retrieve environment variables. So, as long as we preset the required environment variables and fetch them in the program, we indirectly pass the parameters to the program. Let's take a look at the following codeIt seems that there is no text provided for translation. Please provide the text you'd like to have translated.

The declaration of the getenv function is as in Section 4Okay, pass in the name of the variable you want to retrieve, and it will return the value of that variable. If the variable is not found, it will return 0. 10And 15The action involves retrieving the values of two environment variables separately. If the variables are valid, their values will be printed. It is important to note that the values returned by getenv are all strings, requiring the user to manually convert them to numerical types, which makes it less convenient to use. Compile and run:

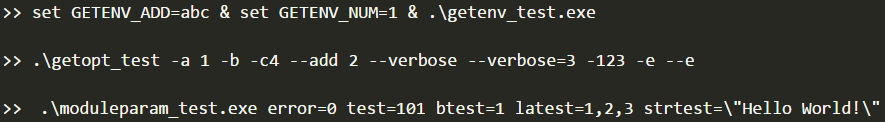

On Windows:

On Linux:

Output:

getopt

Linux provides us with a set of functions getopt, getopt_long, getopt_long_only to handle the command-line arguments passed in. The declarations of these three functions are:

getopt can only handle short options (i.e., single-character options), while getopt_long and getopt_long_only can handle long options. For a detailed explanation of the functions, you can refer to the manual under Linux. Now, let's demonstrate the usage of getopt and getopt_long through examples.

It is important to note that this set of functions is not provided on Windows, so I found a source code that can be compiled on Windows and made a few minor modifications. The code is available here".

Let’s focus on analyzing the usage of getopt_long. The first three parameters of getopt_long are the same as those of getopt, which are: the number of command-line arguments argc, the command-line argument array argv, and the string of short options optstring. The format of optstring consists of short option characters followed by a colon : indicating that an option requires an argument and two colons :: indicate that the argument is optional. For example, in line 19, it declares the form of short options where the b option does not require an additional argument, the a option requires an additional argument, and the c option has an optional argument.

The last two parameters of getopt_long are for handling long options, where the structure of option is:

struct option {

const char *name; // Long parameter name

int has_arg; // Whether it has additional parameters

int *flag; // Set how to return the function call result

int val; // Returned value

};

name can still be set to a single character length.

has_arg can be set to no_argument, required_argument, optional_argument, which represent no argument, required argument, and optional argument, respectively.

flag and val are used together; if flag = NULL, getopt_long will directly return val. Otherwise, if flag is a valid pointer, getopt_long will perform an operation similar to *flag = val, setting the variable pointed to by flag to the value of val.

If getopt_long finds a matching short option, it returns the character value of that short option. If it finds a matching long option, it returns val (when flag = NULL) or 0 (when flag != NULL; *flag = val;). If it encounters a non-option character, it returns ?. If all options have been processed, it returns -1.

Utilizing the characteristics of return values, we can achieve the same effect with long options and short options. For example, if the first parameter add of long_options is set with a val value corresponding to the short option character 'a', then upon checking the return value, both --add and -a will enter the same processing branch, being treated as having the same meaning.

The final missing piece of the puzzle is how to use optind and optarg. optind represents the position of the next argument to be processed in argv, while optarg points to the additional parameter string.

Compile and run the code:

$ .\getopt_test -a 1 -b -c4 --add 2 --verbose --verbose=3 -123 -e --e

option a with value '1'

option b

option c with value '4'

option a with value '2'

option verbose

option verbose with arg 3

option 1

option 2

option 3

.\getopt_test: invalid option -- e

.\getopt_test: unrecognized option `--e'

The meanings of -a and --add are the same. For short parameters, optional arguments directly follow, such as -c4, while for long parameters, the optional argument needs to be preceded by an equals sign, such as --verbose=3.

mobuleparam

Alright, finally we have reached the method that initially inspired this article. The Linux kernel cleverly uses a method called moduleparam to pass parameters to kernel modules. Let me briefly explain how moduleparam works in the Linux kernel here, for a more detailed explanation, you can refer to the code. Although I have borrowed some techniques from moduleparam, there are some differences between mine and Linux kernel's moduleparam. To distinguish, I will refer to my method as small moduleparam, while the Linux kernel's method will continue to be called moduleparam.

Let's first take a look at the usage of moduleparam, declared within the module:

Then enter parameters when loading the module:

The variable enable_debug is correctly set to 1, making it convenient to use. Only a few lines of code need to be added, allowing for concise and elegant coding. There is no need to write extensive loops and conditional statements like when using getenv and getopt. Additionally, it comes with automatic type conversion. Therefore, when I see it, I can't help but think it would be even better if we could use this method to handle command-line arguments.

Next, let's take a look at the core implementation of moduleparam:

module_param is a macro that effectively creates a structure called kernel_param, which reflects the incoming variable. This structure contains sufficient information for accessing and modifying the variable, specifically in lines 20-24, and places the structure in a section named __param (__section__ ("__param")). Once the structure is established, the kernel, when loading the module, identifies the location of the section __param in the ELF file and the number of structures, and sets each parameter's value according to the name and param_set_fn. The method of identifying a specific named section is platform-dependent; the Linux kernel implements this by processing ELF files, and Linux provides the command readelf to view information about ELF files. Those interested can check the help information for readelf.

It was mentioned above that the approach of the Linux kernel is platform-dependent, while I want a platform-independent method for handling parameters. Therefore, we need to modify the original moduleparam implementation by removing the __section__ ("__param") declaration. After all, we don't want to go through the hassle of reading the section from the ELF file. Let's take a look at the modified usage:

So, in order to preserve the structure of each reflection, I added a macro init_module_param(num) to declare the space for saving the structure. num represents the number of parameters. If the actual number of declared parameters exceeds num, the program will trigger an assertion error. The declaration of module_param is slightly different from the original, as it removes the last parameter that represents access permission, which means it does not control permissions. Additionally, a macro module_param_bool is added to handle variables that represent bool. This is not needed in Linux versions because it uses the gcc built-in function __builtin_types_compatible_p to determine the variable's type. Unfortunately, MSVC does not have this function, so I had to remove this functionality and add a macro instead. module_param_array and module_param_string are used to handle arrays and strings, respectively. These two functionalities existed in the original version as well.

Declaration of parameters is complete, now it's time to handle the incoming parameters. Utilize the macro parse_params, passing argc, argv, where the third parameter is a callback function pointer for handling unknown parameters. You can pass NULL, which will interrupt parameter processing when encountering positional parameters and return an error code.

Compile and run the code:

.\moduleparam_test.exe error=0 test=101 btest=1 latest=1,2,3 strtest=\"Hello World!\"

Parsing ARGS: error=0 test=101 btest=1 latest=1,2,3 strtest="Hello World!"

find unknown param: error

test = 101

btest = Y

latest = 1,2,3

strtest = Hello World!

You can see that numerical values, arrays, and strings can all be correctly read in and converted to the required format. If an encountered parameter cannot be converted to the correct format, an error code will be returned along with relevant information being displayed. With just a few lines of code, we can easily handle the input and conversion of parameters in an elegant manner. For a more detailed implementation, you can directly refer to the code here.

Summary

This time we summarized three methods for handling command-line arguments in C/C++, namely getenv, getopt, and moduleparam. Each method has its own characteristics, and in the future, you can choose the appropriate method based on actual requirements.

getenv is natively supported on multiple platforms, so you can use it directly. However, it's quite primitive and relies on environment variables, which can cause some pollution to the environment. It's best to clear unnecessary environment variables before each use to prevent any lingering pollution from previous settings.

getopt is natively supported on Linux platforms but not on Windows, so including implemented code is required to achieve cross-platform usability. The parameter passing follows the standard command line parameter format on Linux, supporting optional parameters, but it can be a bit cumbersome to use. Typically, it requires looping and conditional statements to handle different parameters, and it is not very user-friendly for numeric parameters.

moduleparam is a command-line parameter handling tool inspired by the moduleparam implementation in Linux kernel. It is cross-platform, easy to use, and can perform type conversion for different parameter types. The downside is that each parameter requires a corresponding variable for storage.

Original: https://wiki.disenone.site/en

This post is protected by CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 agreement, should be reproduced with attribution.

Visitors. Total Visits. Page Visits.

This post has been translated using ChatGPT, please provide feedback in FeedbackPlease point out any omissions.